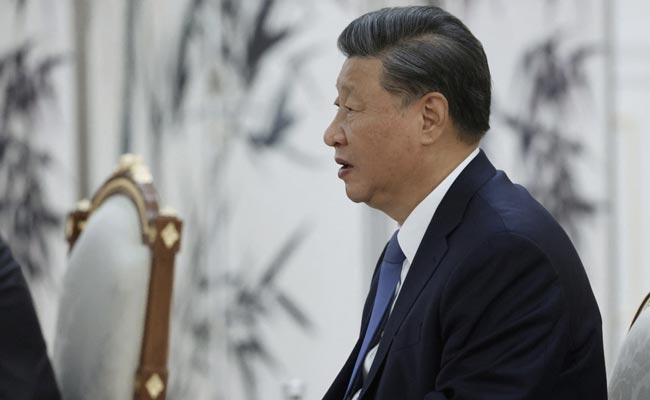

President Xi Jinping meets the media following the 20th party congress in Beijing on October 23. Photo: Reuters

At the 20th Chinese Communist Party Congress, President Xi Jinping showed little or no apparent intention of furthering economic reforms and sent reformers into the backwaters or retirement. The global investor community reacted by selling Chinese shares in bulk.

This new development extends a period of stock market misery that started in the summer of 2021 with Beijing’s regulatory crackdown on platform companies, and gained further momentum with the vagaries of an unsound property sector and unduly harsh enforcement of zero-Covid policies.

Global investors have reasons to be concerned. Xi’s first decade in power has been paradoxical. On the one hand, he tightened state control over the economy and often proclaimed his preference for “stronger, better and bigger” state-owned enterprises (SOEs) but refrained from serious SOE reform, dragging down growth.

On the other hand, the private sector has made striking inroads into the Chinese economy over the past decade, thanks to Chinese entrepreneurs’ and workers’ impressive dynamism. We may now be at a turning point, when the former dynamic becomes dominant. But it’s still too early to be sure.

To have a clearer view of structural trends in the Chinese corporate landscape, we conducted an in-depth analysis of mainland China’s largest companies since Xi was chosen as China’s leader in late 2010.

What we found was a near-continuous increase in private-sector shares of, first, the revenue of China’s largest companies that made the Fortune Global 500 rankings and, second, the market value of the 100 most valuable Chinese listed companies, up until the end of 2020.

An advert by JD.com, one of China’s largest private companies, in Beijing on June 14. Photo: Reuters

In that research, the private sector is defined restrictively as those companies in which the Chinese state holds less than 10 per cent of total equity and voting rights; all other companies are classified as part of the state sector. These categorisations are generally stable over time because both privatisation and nationalisation are infrequent in China, at least among the largest companies.

In terms of aggregate revenue, the private-sector share rose from being basically non-existent in the late 2000s to nearly a fifth in 2020, before dropping slightly to 17 per cent last year, mostly because of higher commodity prices and other one-off factors.

Large private-sector companies now exist in a widening range of industries, including e-commerce and hi-tech manufacturing but also sectors like petrochemicals, metallurgy, appliances, textiles and autos.

EVERY SATURDAY

A weekly curated round-up of social, political and economic stories from China and how they impact the world. GET THE NEWSLETTER

By registering, you agree to our T&C and Privacy Policy

Focusing on listed companies, there has been significant value creation since Xi came to power, and despite his statist policies, it was overwhelmingly a private-sector story. From the end of 2010 to mid-2021, the total market value of private companies among the top 100 listed firms grew twentyfold, while the state sector’s aggregate value increased by just 37 per cent.

During the same period, the share of the private sector in the aggregate market value of the top 100 listed Chinese companies rose from 8 per cent to 55 per cent, an astonishing transformation of China’s corporate landscape. Some of these private champions have undoubtedly benefited from state support and connections, but many are effectively competing with SOEs and there is a strong entrepreneurial dimension behind their rise.

Pedestrians cross a road in the financial district of Shanghai on October 10. Photo: Bloomberg

However, that pattern of private-sector value creation has gone into sharp reversal since mid-2021. Between then and our most recent quarterly observation at the end of September 2022, private listed companies among China’s top 100 have lost more than half of their combined market value, primarily because of the state’s regulatory crackdowns and the resulting loss in value of the country’s internet giants.

The state sector also saw a value drop, but to a much lesser extent. In relative terms, the market-value share of the private sector among the top 100 listed Chinese companies also dropped significantly, from 55 per cent at mid-2021 to 41 per cent at the end of September 2022.

By this yardstick, the private sector’s position among China’s top-ranked listed corporations is now roughly back to where it was in late 2019. In other words, the reversal so far has stopped well short of erasing all of the gains the private sector has made in the previous decade.

New Evergrande protests amid reports troubled Chinese property giant ordered to raze development

Also, the growing diversity of private-sector companies suggests a collective resilience. As of the end of September, internet platform companies only represented 44 per cent of these listed private companies’ aggregate value, down from 73 per cent at the end of 2016. Other companies with a high market capitalisation are in batteries and electric vehicles, bottled water, food flavours, solar panels, medical devices and much else.

As in any research, certain qualifications apply. Market values do not necessarily reflect fundamentals and, more importantly, the data related to the largest companies does not represent the entire Chinese economy.

Altogether, our findings document the magnitude of the private sector’s reversal since mid-2021, but also the fact that it remains considerably larger and diverse than at the start of Xi’s era. Whether the recent private-sector retreat is temporary or permanent remains to be seen. The outcomes of the party congress and the market reactions are not encouraging.

Tianlei Huang is a research fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). Nicolas Véron is a senior fellow at PIIE and at Bruegel

scmp.com