By

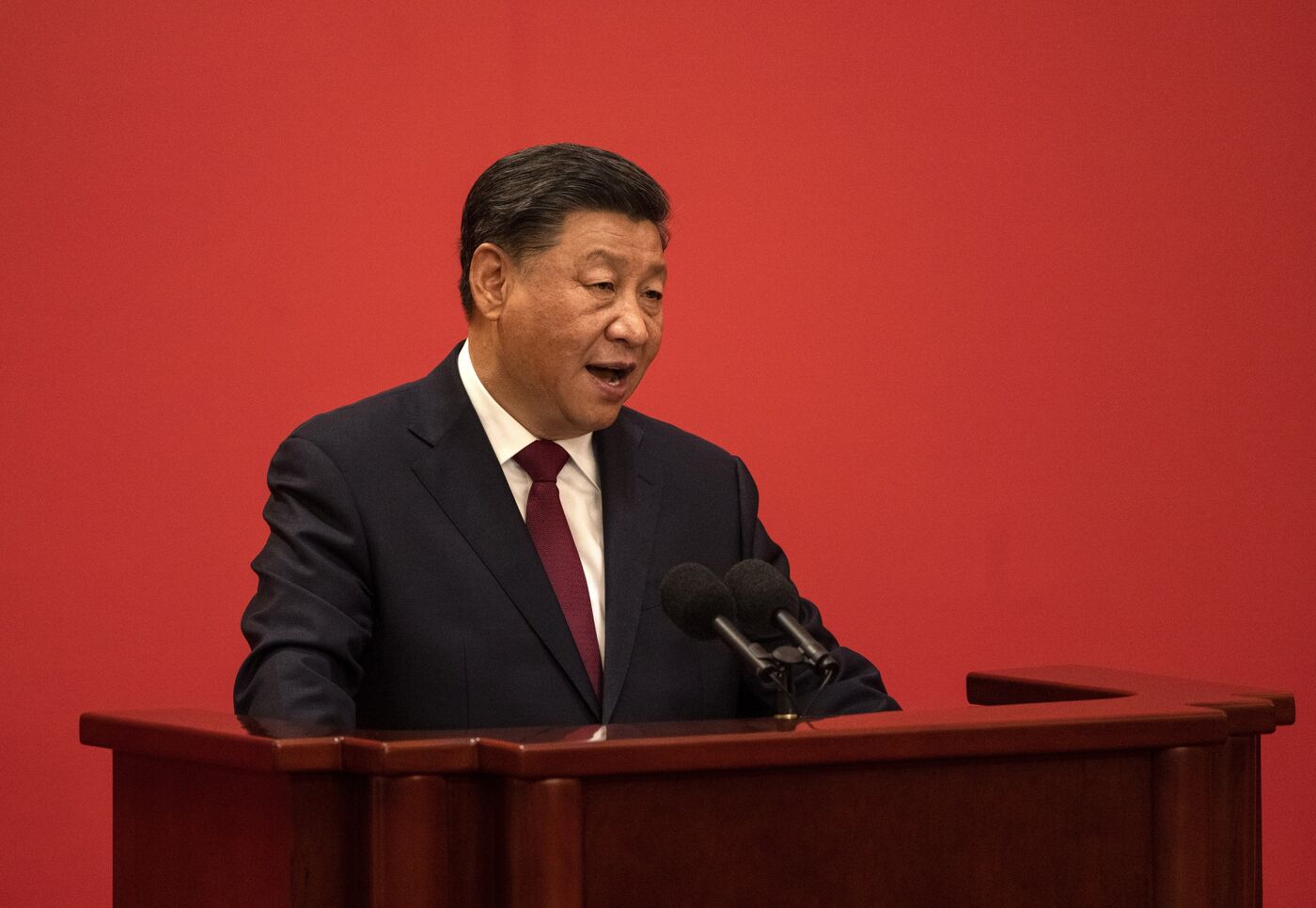

The beginning of Xi Jinping’s third term in power has been marked by a bitter intellectual war between advocates of state ownership and planning, and those touting private businesses and markets.

The public debate among senior economists centers on the merits of a return to a Mao Zedong-inspired “people’s economy.” It’s witnessed otherwise-mundane news items about rural cooperatives and public canteens, features of the Mao-era economy, suddenly going viral online.

The debate underlines a widespread uncertainty in China about where the nation is headed under Xi. And that itself is a drag on an economy already in the doldrums due to the pandemic and a housing slump.

Those on China’s “left,” including so-called Neo-Maoists who are nostalgic for a centrally planned economy, have been facing off against those on the “right” who’ve supported the private sector since at least 1992. That’s when Deng Xiaoping endorsed the ambiguous formulation that China is a “socialist market economy.”

Private Sector Pessimism

Measures of Chinese private business confidence have fallen this year

Xi continued to use Deng’s slogan at the Communist Party congress last month. He asserted the importance of private companies and advocating reforms to increase the role of markets in the economy. He also called for stronger state-owned companies and “common prosperity,” which is seen as a leftist slogan.

The spark for the current iteration of the debate came a few weeks ahead of the congress. That’s when a video of veteran agricultural scholar Wen Tiejun calling for a “people’s economy,” interspersed with footage from the 1960s, began spreading online.

Some elements of Wen’s proposal, such as boosting self-reliance in technology and supply chains to preserve sovereignty, are in line with Beijing’s policy. But his call for more emphasis on public ownership is what set off the fireworks.

“Xi Jinping’s heightened discourse on economic security and ‘common prosperity’ have sent a signal to intellectuals like Wen Tiejun that there is an opportunity to nudge the policy discussion in the direction of China’s socialist roots,” said Jude Blanchette, author of a book on China’s neo-Maoists.

One popular online article compared the supporters of the “people’s economy” to “antiques crawling out of the grave of history.” Prominent economists like Ma Guangyuan of Peking University and Ren Zeping, formerly of Soochow Securities Co., also bashed Wen’s proposal.

The left fired back. While the debate might scare the private sector, that only reveals its “guilty conscience,” an article on prominent Neo-Maoist website Utopia proclaimed.

Weighing in after the party congress was Jia Kang, a government adviser linked with China’s finance ministry. China’s online debate has become “polarized” and “irrational,” he said in a speech. Attempts to deny the role of markets in the economy are “extreme and unacceptable,” he added.

He criticized Wen and his supporters for downplaying the contribution of foreign investment and trade to China’s development. The Communist Party settled the debate over markets in 2013, saying they should play a “decisive role” in allocating resources.

Jia was following up on a line of criticism from Li Xiaoxi, a former director of economics at one of China’s top state-run think tanks, who emerged from retirement to call Wen’s proposal “worrying.”

Even talking about a return to 1950s-style economic policy will damage China’s international reputation and undermine private business confidence within China, Li said.

That’s crucial: private business confidence in China is at a low ebb, according to independent surveys. As a result, private investment is slumping too. The threat of sudden lockdowns under the “Covid zero” policy is the main factor, but the debate doesn’t help.

And these issues aren’t just resonating with intellectuals.

An article calling for strengthening China’s system of “supply and marketing cooperatives” —state-owned companies that buy and sell goods from farmers in rural Chinese areas—was taken by many casual readers to signal a return to Maoist communes. With lockdowns this year, local governments have been directly distributing food to citizens, and reports about “community canteens” went viral.

It was quickly pointed out that the canteens were a single-province initiative, and while the cooperatives have always been a part of China’s rural economy, they aren’t going to replace private retailers. Even so, the virality of the articles arguably underlines the widespread uncertainty.

China’s state sector share of GDP has stabilized since the late 1990s

Source: Andrew Batson, Gavekal Dragonomics

Note: “SOE” refers to state-owned enterprises

It’s possible Xi could be puzzled by the resurgence of this debate. The contribution of the state sector to GDP has remained largely constant under his rule, at least up to the pandemic, according to research by Andrew Batson of Gavekal Dragonomics.

And the party last year released a landmark “historical resolution” that re-affirmed that key Maoist policies such as “people’s communes” were a “mistake.”

“While much of Xi’s rhetoric is to the liking of leftists, after 10 years in power, he has demonstrated himself to be more State capitalist (with a capital s) than a true socialist,” Blanchette said.

One universal feature of China’s intellectual war is that everyone seems to feel like a victim. The tone of economists like Jia Kang suggests they feel somewhat under siege, while a response to the agricultural cooperatives debate posted on Utopia suggested the left feels defeated, too:

“I can see this kind of crap almost every few years. Speaking honestly, I am looking forward to something really happening,” the article read, referring to previous calls for nationalization of the private sector. “In fact nothing happened. Instead of robbing private businesses…a bunch of debt-ridden private companies were rescued,” it added.

In the absence of a direct response from Xi, that’s the closest we can get to a litmus test for now: as long as both sides are unhappy, the party’s ambiguous compromise between state and market is probably continuing as before.

bloomberg.com