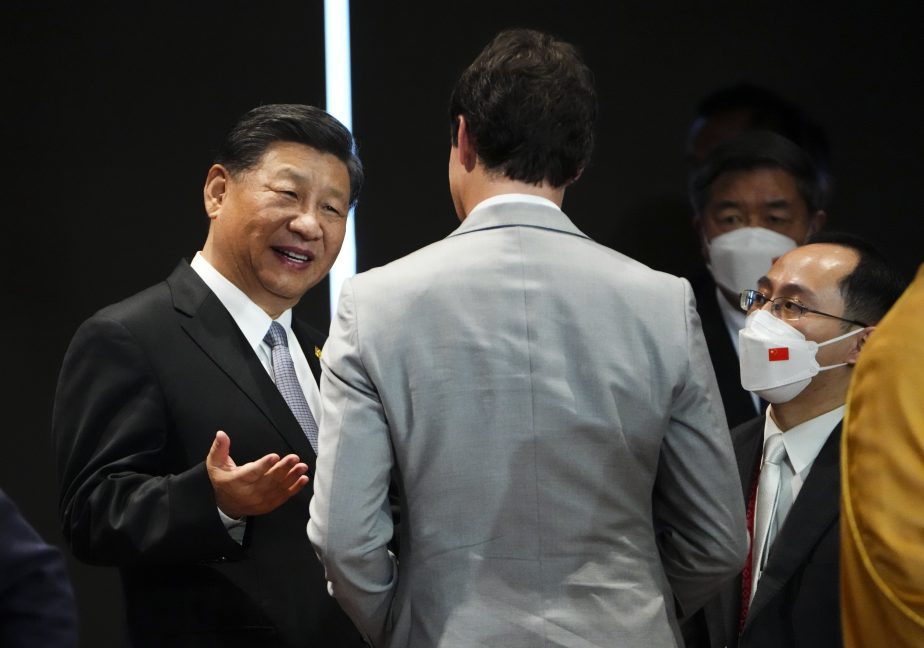

The Canadian press pool caught a heated exchange on camera at the G-20 summit on November 16. Walking up on a sideline chat, a reporter found Chinese leader Xi Jinping criticizing Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau: “Everything we said has been leaked to the papers. That’s not how the conversation was conducted.” Xi continued, “If you are sincere, we should communicate with each other in a respectful manner. Otherwise it will be hard to say what the result will be.”

In response, Trudeau said Canadians believed in “free and open dialogue” and would “look to work constructively together,” although there would be “things we will disagree on.”

Capturing such a candid exchange between world leaders is unusual enough, but the insight it offers into Xi’s unguarded thoughts is rare indeed.

Xi was apparently dissatisfied that an unnamed source had released certain details of a conversation he and Trudeau had the day before on the sidelines of the summit. In the original conversation, Trudeau expressed “serious concerns” over Chinese government interference in Canada’s elections. There had been little ado over the exchange initially: Commentators compared Trudeau’s 10-minute chat with Xi unfavorably with U.S. President Joe Biden’s three-and-a-half-hour talk.

Some media sources noted that Xi, walking away from the exchange, seemed to exclaim “so naive.” The interjection shows his emotional involvement in the topic, specifically frustration with Trudeau. Outsiders may not immediately understand his sentiment. How is Trudeau being “naive” by discussing China’s election interference?

The most direct explanation is that Xi cannot imagine any leader would sacrifice their country’s relationship with China for the sake of “openness.” His implied threat is that China will pressure Canada economically, for example by halting Canadian exports, as it has attempted with Japan, Australia, and Lithuania among others. In each case, China inflicted temporary economic pain but, arguably, lasting ill will.

China’s diplomats have displayed a similarly pugilistic tone in recent years, outdoing themselves to please Xi. Historian Roderick MacFarquhar labeled a similar phenomenon during the Mao era as “working toward the Chairman.” In a recent essay, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi described this as “great power diplomacy with Chinese characteristics,” exhorting diplomats to “carry forward the spirit of struggle,” “demonstrate a will and determination that fears no power,” and “resolutely counter any erroneous acts that infringe on our sovereignty.” Contrary to ordinary conceptions of diplomacy, China’s diplomats are willing to sacrifice China’s reputation and relationships on the altar of Xi’s approbation.

But this begs the question of Xi’s motivations, and I believe there are several. First, some would call him an “image junkie,” keenly attuned to protecting China’s and his own image. Xi may have felt blindsided or betrayed when, after speaking privately, the Canadian government appears to have released information placing Beijing in a negative light. The reputational damage of threatening Trudeau in response seems not to have figured in Xi’s image equation.

Some commentators judged Trudeau mistaken, believing the prime minister had in fact released details in violation of protocol, even though these consisted of no more than the topics of discussion. It is customary not to discuss the details of official exchanges outside the governments concerned, but this custom has limits. The fact of two leaders meeting is not generally considered secret, nor is some statement concerning the content of such meetings. Xi’s own government (like many others) routinely releases the agenda items of otherwise private conversations. This makes Xi’s claim of a “leak” seem specious.

China’s tabloid Global Times prefigured Xi’s thoughts in an earlier editorial, claiming Canada “surrenders its sovereignty” to the United States and that “blaming China can’t save declining Canadian democracy.” Xi has previously expressed similar disdain for the United States. Global Times also seemed to explain Xi’s vague threat: “The Canadian PM is making uncalled-for troubles against China, which is bound to affect bilateral relations.”

Some went so far as to cheer the sight of a leader of the developing world rebuking the supposed arrogance of a “Western” world leader (China still claims to be a “developing country,” despite being one of the most powerful in the world). For them, Xi “gave a dressing down” or “put Trudeau in his place.” Others described Trudeau’s conduct as exemplary and felt he had stood his ground.

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning insisted this was a “normal” exchange, not any sort of confrontation. In light of Xi’s threatening outburst, one commentator labeled Mao’s statement “damage control,” although any mitigation she may have achieved was undone by saying Trudeau had acted in a “condescending manner.”

Importantly, Trudeau’s topic could not have come as a surprise to anyone else. Just a week earlier he had publicly decried Chinese interference in Canadian elections. Xi’s consternation suggests he did not know of this and expected Trudeau to keep it a private matter, with some implication that Xi might act on it later as a special favor, perhaps by reducing the degree of China’s interference.

From Trudeau’s perspective, Xi’s drive to keep unfavorable news about threatening behavior from Beijing a secret would be completely unacceptable. The fact that Xi expected Trudeau to do so – enough so to trigger a scolding before an international audience – hints that the Chinese leader was inadequately briefed on the topic and his understanding of perspectives beyond CCP orthodoxy is limited.

By the standards of democratic society, Xi’s feeling is bizarre. Free elections and freedom of expression, including of the press, are basic democratic rights that representative governments are bound to protect. That being the case, it is doubtful Trudeau had any authority to cover up the threat of Chinese election interference in the first place. Even if Trudeau had made strenuous efforts to keep it a secret, it would likely have gotten out anyway.

The ultimate irony of the incident is that Xi’s upbraiding of Trudeau for making China’s spying public was perhaps the most public aspect of the affair. Xi thus led his “wolf warriors” in portraying China as a bully. Outsiders have too often downplayed such hostile words as aberrations. Let Xi’s reproach leave no doubt. As business leaders from democratic countries court China’s goodwill, they must weigh the significant risks posed by Beijing’s brazen claims and totalitarian abuses. Xi’s mindset shows these are only the beginning.