A gargantuan hangar in a secretive Xinjiang desert reveals China is thinking big – really big – when it comes to high-altitude warfare.

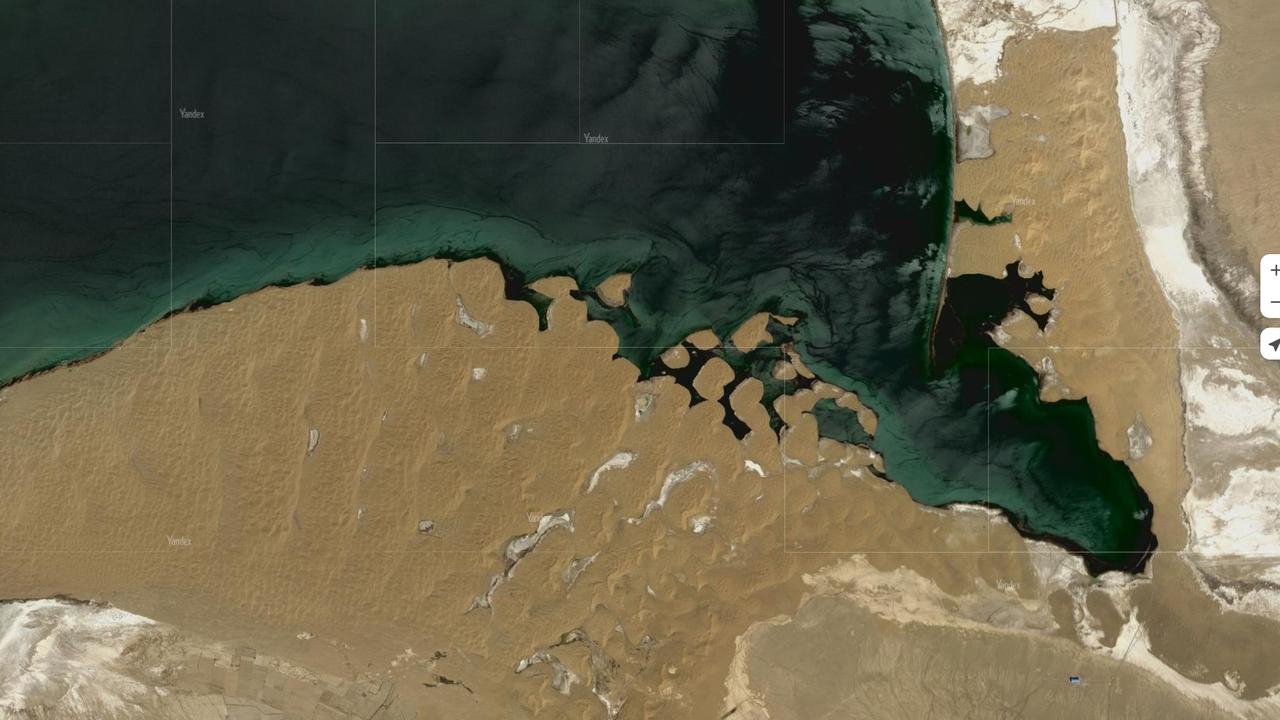

Open-source intelligence (OSINT) analysts have been tracking the construction of a giant hangar on the northern edge of Xinjiang’s Taklimakan Desert since 2013. That’s when the People’s Liberation Army cut the foundations of a colossal new building into the sands of a research facility to the southeast of Bositeng Lake.

Its shape was familiar. But its size was unexpected.

It’s now one of the largest hangars anywhere on Earth.

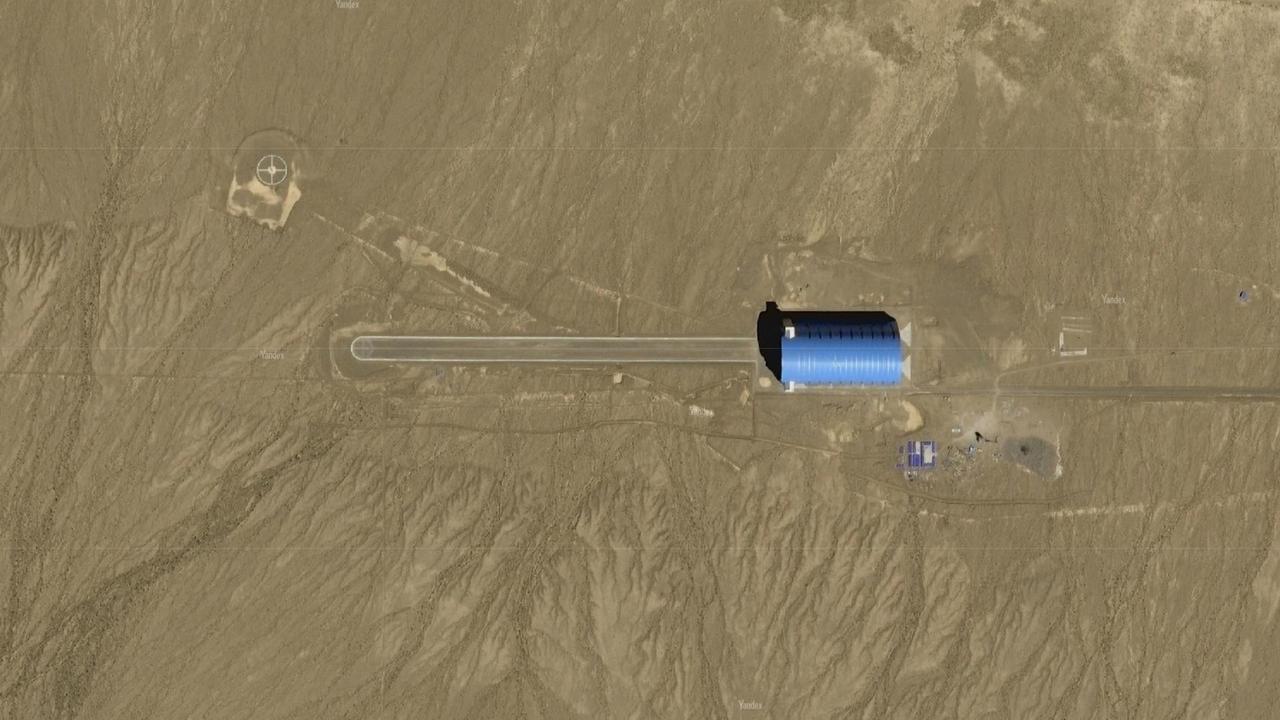

The 350m by 140m structure appears to have been completed in 2015, though what it contains has yet to be captured on a commercial satellite image.

However, a new analysis by The War Zone blog has uncovered some helpful hints.

Specifically, it spotted a sizeable rectangular cradle sitting on a 1km long apron just outside the hangar’s doors. It’s most likely a sled designed to move a vast lighter-than-air craft into the clear to be launched.

Stream your news live & on demand with Flash. From CNN International, Al Jazeera, Sky News, BBC World, CNBC & more. New to Flash? Try 1 month free. Offer ends 31 October, 2022 >

The facility is in the middle of nowhere – a remote Xinjiang desert alongside a salty lake. The huge hangar can be seen in the bottom right corner. Picture: Yandex.

Airships are nothing new. Attempts have been made to exploit their size and simplicity for centuries – almost always with catastrophic consequences.

Now, however, Beijing appears to be banking on new technologies to finally bring the concept to maturity.

“But any article about the prospects for a new golden age of airships needs to carry a substantial caveat: Not only have we been here before, but we seem to come back to this space every few years,” argues analyst Jacob Parakilas in The Diplomat.

This 2013 satellite photo on Google Maps shows the foundations of what will become the hangar being cut into the Xinjiang desert. Picture: Google Maps

A recent, although undated, satellite image of the mysterious hangar, its apron and nearby structures. Source: Yandex

Flying high

“Although there are no further publicly available details about what kind of vehicle will call the hangar home, its giant dimensions seem to strongly suggest a lighter-than-air craft of some type,” says Parakilas.

Any such airship won’t look anything like the famous cigar-shaped Zeppelins of the early 1900s.

Modern hybrid designs are built to a ‘lifting body’ shape. That means the entire structure acts like a cutaway section of a wing. Fins give the squat vehicles stability and steerage, as do a variety of strategically-placed thrusters.

The bigger they are, the more they can carry – higher and longer.

A Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV) concept image showing a hybrid airship design using a city’s existing port facilities. Picture: HAV

And that’s a characteristic that has appealed to militaries worldwide for more than a century.

“Nowadays, a stratosphere airship sows its origins from earth observation, maritime monitoring, missile warning, communication signal relays,” a 2018 Chinese Journal of Aeronautics research paper states.

“It is mooted as an affordable part substitute for a near-earth orbit satellite or can eliminate the need for multiple aircraft sorties to sustain continuous on-station keeping.”

The interior of one of Russian billionaire Sergey Brin’s Lighter Than Air (LTA) hangars. Picture: LTA

That’s especially useful for surveillance.

Radars, cameras and data-intercepting sensors can be hoisted far above ground-based clutter and interference. And they can be moved to where they are needed most.

It’s also useful for Low Earth Orbit (LEO) operations.

Giant airships can theoretically sit 20km above the surface, on the edge of space. Here they are much closer to earth observation satellites and essentially free of ground-based interference.

That would prove an advantage in any electronic-warfare intense conflict.

But such airships would also be ideally placed to jam or shoot down opposing satellites – or potentially even ballistic missiles.

Troubled history

In May, Chinese state-controlled media announced that its observation airship “Jimu No. 1” type III had reached a new record altitude of 9032 metres while flying over occupied Tibet.

Such craft remain in use as weather observation platforms, advertising frames and media camera carriers. But drones are rapidly taking over even these roles.

So far, airships have failed to live up to their promise.

They are light. They are fragile. They’re prone to devastating and fatal accidents.

“A series of catastrophic accidents – culminating with the iconic, fiery end of the Hindenberg – put an end to the era of giant, rigid airships right before the outbreak of World War II,” says Parakilas.

A hybrid airship cruiser liner design by Ocean-Sky. Picture: Ocean-Sky

Since then, attempts to revive airships have arisen every decade or so, only to meet similar fates.

One more recent US military attempt was abandoned in 2014. The High-Altitude Long Endurance-Demonstrator (HALE-D) had crashed on its first flight – destroying the high technology payload it was carrying.

That’s still not deterred ambitious attempts to overcome the airship’s greatest enemy – the wind.

And their inherent fragility.

Russian billionaire Sergey Brin’s company Lighter Than Air (LTA) is also aspiring to build enormous new airship designs as cargo carriers and luxury liners, as are a series of businesses in Britain and the United States.

Future tense

Modern materials science is producing alloys and composites far more robust and lighter than aluminium. New electric engines are far more powerful. And integrated solar panels can potentially keep a craft in the sky indefinitely. Especially if they exploit hydrogen fuel cells over heavy lithium-ion batteries.

“That said, there are real technical obstacles still to be overcome,” argues Parakilas.

Helium is a non-renewable resource. World stockpiles are low and expensive.

Hydrogen is a more efficient lifting gas. It’s also extremely flammable.

A concept Roll-On Roll-Off (RORO) heavy-cargo carrying hybrid airship. Picture: Varialift

But that’s likely less of an issue in a world of uncrewed, autonomous drones.

“Hypothetically, there could be an airship lifted by a vacuum — that is, by material that can contain nothing at all inside but withstand the atmospheric pressure from the outside,” analyst Justin Ling argues in Foreign Policy.

“It is, at this point, science fiction.”

But the ability of airships to efficiently carry heavy cargo and deposit it anywhere – unlike trucks, helicopters or cargo aircraft – is becoming increasingly appealing.

“Cargo airships may actually make a tremendous amount of sense,” says Ling

“They are relatively cheap, they can carry enormous amounts of material, and they emit significantly less greenhouse gas than other modes of transportation.”