For years, Abduweli Tursun had no idea what happened to family members back home.

He had fled to Turkey in 2014 as Chinese authorities cracked down on the mostly Muslim population in the far western Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, supposedly to suppress terrorism and religious extremism.

Living in Istanbul and working as a trader, Tursun, 39, would scour social media for news about people back home but almost always came up empty.

But earlier this month, he discovered an amazing online tool called the Xinjiang Police Files Person Search Tool. By typing in names, he could see mugshots of several family members and neighbors in his hometown of Tashmiliq in Konasheher county, and find out their detention status, reasons for detention and prison sentences.

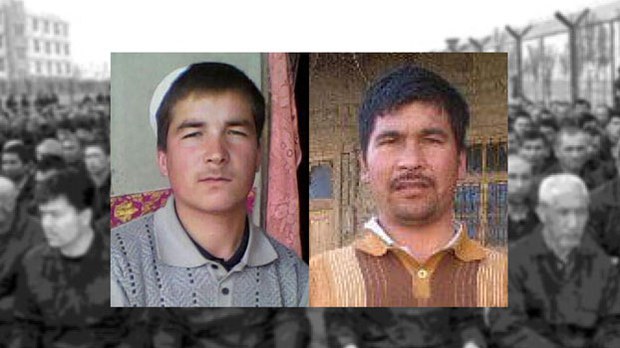

But any relief at locating loved ones was overshadowed by despair when Tursun learned that two of his brothers, Hoshur and Mahmut, sister Nuriman and other friends had been given long prison sentences.

One brother was sentenced to 18 years in prison for sending Tursun money when he was in Malaysia, en route to Turkey. Nuriman was arrested simply because Tursun had fled.

“My heart ached after seeing each receive a lengthy prison sentence,” he told Radio Free Asia.

All told, he found data on about 20 individuals in his hometown.

“I left my hometown long ago,” he said. “I could not recognize some.”

Hacked from police computers

The search tool was unveiled on Feb. 9 by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, a U.S.-based nonprofit organization. People can use it to search over 700,000 personal records of Uyghurs and Kazakhs who were among the total 830,000 individuals included in the Xinjiang Police Files, a cache of millions of confidential documents hacked from Xinjiang police computers.

The tool allows anyone to enter names in Chinese characters or national ID numbers into a search engine to find out details about them in files that date from 2017 to 2018, the height of one of China’s “strike hard” campaigns, during which hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs and other Turkic minorities were sent to the “re-education” camps.

Someone anonymously sent the data to Adrian Zenz, director of China Studies at the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, earlier this year. Zenz has spent years documenting China’s abuses against Uyghurs.

“It’s as if you can log into a Xinjiang police computer and get data output from the police itself, like what they have on the person [whose name] you enter,” Zenz said. “And in the 5 million records, we identified over 700,000 different individuals that have data on them.”

China has held up to 1.8 million Uyghurs and other Turkic peoples in the detention facilities in an effort to prevent “terrorism” and “religious extremism,” with some subjected to torture, sexual assault and forced labor.

In May 2022, Zenz released information about the leaked records that appear to be from internment camps, with photos of and information about detainees. He also released classified speeches by high-ranking Chinese Communist Party officials describing Uyghurs and other Muslims as an “enemy class” whose traditions must be eradicated for China to survive.

Sheds light on China’s abuse of Uyghurs

The data sheds more light on Beijing’s human rights abuses in Xinjiang and provides more evidence of the repression of the Uyghurs, adding pressure to other countries and the United Nations to hold the Chinese government to account.

The Chinese government has repeatedly denied committing rights abuses in Xinjiang and has angrily denounced Zenz and his findings.

Tursun learned about the Xinjiang Police Files Person Search Tool when he came across a list of photos of detained Uyghurs posted on Facebook by activist Abduweli Ayup, who is from the same county as Tursun, but now lives in Norway.

“He provided information on about 10,000 people detained in our county, Konasheher,” Tursun told RFA. “I can’t read Chinese, so I asked people fluent in Chinese for help and obtained information about my relatives, acquaintances and neighbors. That is how I found them.”

Complete sets of data can be found for the entire populations of Konasheher in Kashgar Prefecture and Tekes county in the Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture, and partial information for residents of all ages from dozens of other counties in Xinjiang, he said.

While most reasons for detention relate to purported acts of “religious extremism,” contact with Uyghurs or others living outside Xinjiang, or religious teachings found on their mobile devices, Zenz said he was surprised that many detained Uyghurs were listed under a bizarre “untrustworthy people” category because their whereabouts could not be determined or because they went out at night.

“One person who was detained for reeducation because she supposedly engaged in unusual nightly activities, and her phone was frequently turned off,” he said.

Others were detained under “913,” which Zenz believes might refer to a date on which mobile operators were testing phones to see who had their handsets turned off or had supposedly unusual activity on them.

The search tool also has an integrated digital form for relatives of detainees who want to submit complaints about violations of human rights treaties to the U.N. Special Procedures, independent human rights experts with mandates to report and advise on human rights from a thematic or country-specific perspective.

“Basically, if your relative or family member or somebody you know has been a victim of the atrocity and there’s some evidence in the police files that indicates that they have been victimized in some way, then you can make a submission to the United Nations Special Procedures,” Zenz said.

The U.N. Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights said in an August 2022 report that “serious human rights violations” committed in Xinjiang may constitute crimes against humanity.

Translated by the Uyghur Service. Edited by Roseanne Gerin and Malcolm Foster.