Ian Bremmer is president of Eurasia Group and GZERO Media and author of “The Power of Crisis.”

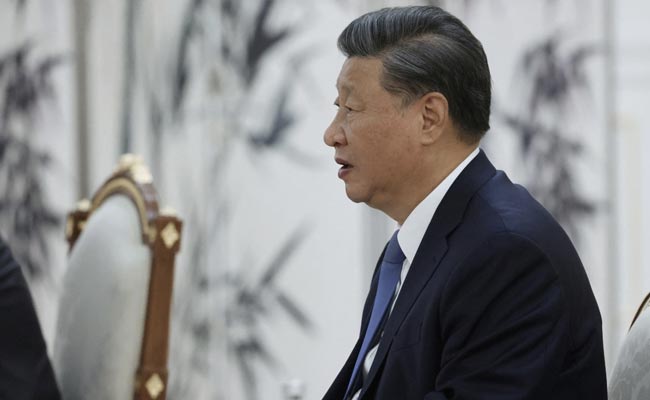

Xi Jinping’s ability to make arbitrary decisions that impact the lives of billions of people is now unrivaled, following his emergence from last year’s Communist Party national congress with tighter control over both the ruling party and China than any leader since Mao Zedong.

This has enabled Xi to continue his state-centric approach to China’s economy and an overtly nationalist foreign policy with even less internal resistance than he has encountered since beginning his consolidation of power a decade ago.

Because China is exponentially more important for the stability of the world economy and the balance of geopolitical power than during Mao’s reign, Xi’s power has become a global problem.

Consider a few of his recent decisions. His refusal to import foreign-made mRNA vaccines has left China’s 1.4 billion people far more vulnerable to COVID-19 than they should be.

To date, COVID deaths in China amount to a small fraction of those seen in the U.S. or Europe, but there is good reason to fear that this remarkable success, which has been economically and socially costly, cannot last.

Add in China’s failure to adequately vaccinate people even with locally made vaccines. Millions are at risk of severe disease or worse.

Xi’s drive for control has produced considerable damage in other areas, as well.

A secretive crackdown on private-sector technology companies, probably driven by fears they have too much influence over the flow of information in the country, has undermined China’s ability to build groundbreaking new digital technologies and the confidence of international investors that China remains a safe place to invest. This has drained away a trillion dollars in market valuation from one of the most efficient areas of China’s private sector.

On foreign policy, Xi’s announcement of a “no limits” friendship with Russia just three weeks before the invasion of Ukraine has exacerbated fears in America and Europe that he shares President Vladimir Putin’s hunger to remake the international system.

In each case, Xi’s authoritarian personality, his drive for tight political and economic control and his hawkish approach to foreign policy have overridden the wise counsel he might have received from within the state bureaucracy.

And these moves came before Xi crowned himself emperor last October by filling the Politburo Standing Committee with trusted loyalists and discarding the post-Mao consensus of rule by committee.

Now that Chinese policy flows directly from a single all-powerful leader, there is even less transparency in the decision-making process, less reliable information flowing to the top to inform that process and less room to admit error, change course or even compromise.

The problem of “maximum Xi” will grow larger in 2023.

First, the startling decision to end zero-COVID all at once and without careful preparation could kill a million or more Chinese people.

The snap decision to allow the virus to spread unchecked, particularly while vaccination rates among the elderly remain dangerously low, was made without warning citizens or even local governments. It is creating deadly chaos that the government has tried to hide from the outside world and its own people.

Only an emperor could execute such an extraordinary and extraordinarily costly reversal.

If a dangerous new COVID variant emerges, maximum Xi makes it more likely that it will spread quickly across China and beyond. China’s ability to identify new variants has been compromised by Xi’s order to sharply and suddenly reduce testing.

We should also fear that China’s hospitals were not prepared for the waves of seriously ill people they have begun to accept. Nor can the world have confidence, given COVID’s origins in late 2019, that China will share information about the virus’ evolution needed to protect lives outside its borders.

On the economy, Xi’s drive for state control will produce decisions unchallenged by expert opinion and unaffected by a surge in policy uncertainty. This will be bad news for an economy already weakened by three years of COVID lockdowns, falling confidence in the all-important real estate sector and debt defaults that could undermine the country’s financial sector.

Beijing’s handling of economic statistics will also face scrutiny. A sudden decision to delay the release of long-scheduled economic data during October’s party congress was an ominous sign of things to come for global markets.

Finally, on foreign policy, Xi’s nationalist views and assertive style will define Beijing’s relations with rivals, allies and the very large number of governments that are deeply reluctant to risk becoming either.

Xi knows his country cannot afford a near-term crisis, given the scale and immediacy of the economic challenges at home. But “wolf warrior” diplomacy will intensify nonetheless as diplomats echo Xi’s aggressive foreign policy rhetoric.

Xi’s personal affinity for Putin and his worldview will limit how closely China engages with governments that support Ukraine. More destructive Russian behavior, a virtual certainty in 2023, will color U.S. and European attitudes toward Xi and China.

The last time a Chinese leader had this much unconstrained power, the result was widespread famine, economic ruin and the deaths of millions of people. There is no Cultural Revolution or Great Leap Forward on the horizon, and the size of China’s educated urban middle class provides one of the few checks on Xi’s ability to take drastic measures. But maximum Xi has already cost China and the Chinese people a great deal, and it will likely cost them even more in 2023.

asia.nikkei.com