After much delay, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken travels to China this weekend, hoping to prevent U.S.-China tensions from spiraling further. The bilateral relationship remains the focus of intense attention, but multilateral organizations have long been sites of U.S.-China conflict. The latest arena is UNESCO, which the United States just announced plans to rejoin, largely to counterbalance China’s influence on it.

The United States pulled out of the organization in 1984, citing Soviet influence, and returned in 2004 only to leave again during the Trump administration. It wasn’t just Cold War politics that drove the United States (and the United Kingdom) out of UNESCO in the 1980s. The organization’s internal corruption and bureaucratic incompetence gave it a poor reputation within the nongovernmental organization sector that lasted well into the 2000s.

Things at UNESCO have changed in the decades since, especially after the election of Audrey Azoulay—who has a reputation as a competent manager and diplomat—as director-general in 2017. But disagreements that caused the Obama administration to withdraw funding under an existing law in 2011 and the Trump administration to withdraw altogether were about UNESCO’s recognition of Palestine rather than core U.S. interests. Like China’s pettiness over recognition of Taiwan, the U.S. moves seemed self-sabotaging.

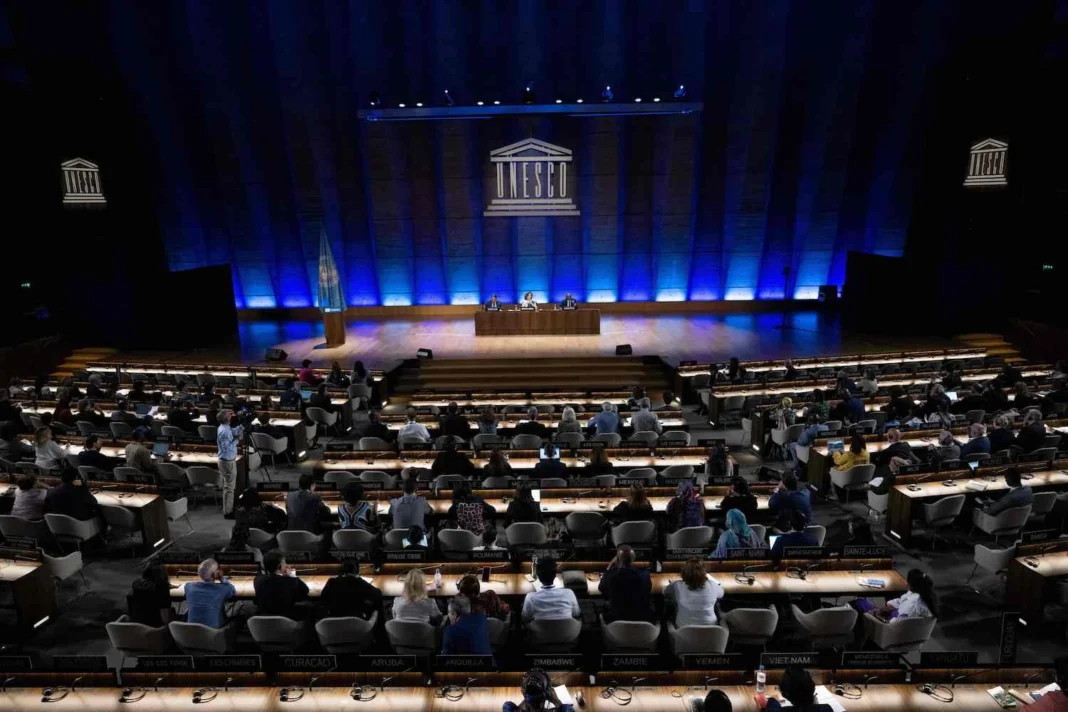

Although UNESCO isn’t a major geopolitical player, the U.S. absence has—to name one example—aided China’s politicization of UNESCO’s Intangible Cultural Heritage list, claiming minority customs and art as part of Chinese heritage or appropriating neighbors’ traditions. (FP’s Liam Scott reported on China’s strategic use of UNESCO’s cultural heritage designation earlier this year.)

The United States returning again should give UNESCO a big financial boost; it owes $600 million in membership back fees. Ultimately, the U.S. relationship with UNESCO highlights a fundamental advantage that China has within the United Nations: Beijing keeps showing up. China has successfully promoted the election of its own staff to key roles in the U.N. and other international organizations, whereas in the United States, domestic politics sometimes get in the way.

Washington gets in its own way on other issues, too; it might set up an international trade deal only to have both presidential candidates promise to abandon it during the next election cycle, for example. Meanwhile, the very nature of the United Nations plays to Chinese officials’ strengths. It is a highly bureaucratic organization where suspicion between members abounds; in other words, it resembles the Chinese Communist Party.

China’s own internal politics can sometimes frustrate it on the international stage. Yet Beijing recognizes power depends on showing face at every meeting and sitting through every speech. And compared to China’s bilateral relationships—where it often abruptly breaks off relations or ends talks—its role in multilaterals is much more consistent, because it sees “discourse power” as crucial.

foreignpolicy.com