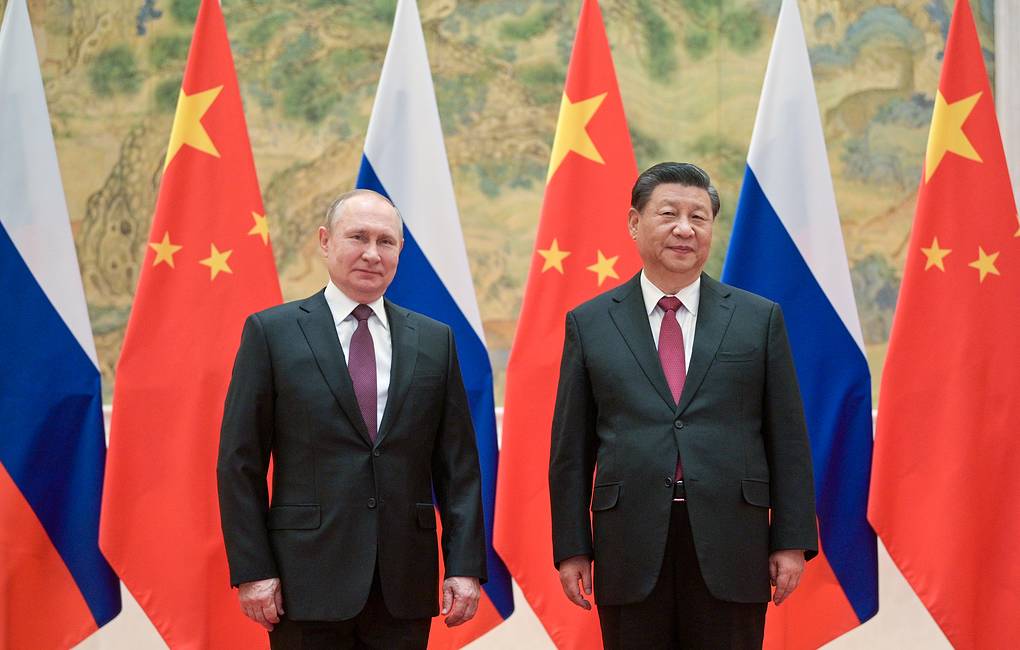

Six months into the Ukraine conflict, China appears to have caught Russia in a friendly web of its own. On the one hand, it gives the impression to Russia that the latter can continue to mint its imperial ambitions. On the other, China extracts more than its pound of flesh in terms of huge concessions.

When President Vladimir Putin was readying to attack Ukraine, China was the only country that backed him. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi said at that time that «Sino-Russian strategic cooperation has no end limits, no forbidden areas, and no upper limits». Putin finds himself bolstered by China’s open backing as he continues to attack Ukraine, play ball with Europe over gas and oil supply, sell oil at discounted prices to various countries thus negating the impact of the US sanctions. By the same token, there are many Western military strategists who suspect that Putin may have already found a second target in Kazakhstan after Ukraine. Friction is growing between them since the beginning of the year, when the Central Asian country witnessed the most violent riots since its independence in 1991. Russia is unhappy that the Kazakhs are not expressing enough gratitude for Moscow putting down the January uprising. Growing nationalism in Kazakhstan is forcing ethnic Russians to escape the country. Kazakhstan is trying to woo foreign companies leaving Russia over Ukraine. Finally, Kazakhstan is yet to publicly back the Russian invasion. As Russia tries to handle Ukraine on the one hand, the antagonistic West on the other, and nurture its future expansion plans on another front, one may wonder if the Kremlin is now feeling the pinch of having the unfettered backing of China. Russia is only now beginning to realise that while its stance against the United States and the West may have brought it strategically close to China, the real strategic effect for Russia is an increasing reliance on China itself.

Defense One, a US military and defense news outlet, recently pointed out that the “Chinese Communist Party leaders have shown no qualms about using this growing dependence to their advantage. China has increasingly dictated the direction of the partnership and squeezed more concessions from the Russians, hiking up prices and walking a diplomatic tightrope with Western nations from which it can’t afford to commercially detach. Rather than making Russia great again, as hoped, President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine has instead deepened Russia’s position as the clear junior partner in the Sino-Russian relationship, militarily and economically.” For instance, military cooperation between the two countries has not increased since the Ukraine conflict began. It is still in the beginning stages. “China and Russia held their first joint military exercise since Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine on May 24, with both countries sending out nuclear-capable bombers while President Joe Biden visited the region. In July, People’s Liberation Army troops, tanks, and vehicles set out for Russia to participate in the so-called ‘War Olympics’. China has also indirectly supported the Russian war machine by exporting off-road vehicles for transporting command personnel, as well as drone components and naval engines.”

Apart from a certain extent of Russian reliance on Chinese military vehicles, the relationship has benefitted China in the defense market. “In 2014, Western sanctions gave Russia’s military industrial complex new impetus to sell technology to the Chinese PLA. Today, the Kremlin has even fewer customers or partners, and its reliance on China’s technology after its Ukraine invasion could accelerate burgeoning joint development and operations, if only for a while. In the long term, Russia’s struggling arms manufacturers cannot bet on China to sustain or grow them.”

As Russia’s defense market dries up, China’s defense companies are aggressively pursuing new markets across the world. In recent years Beijing, especially this year, increased its share of the global arms trade to 4.6 per cent, making it fourth behind the United States, Russia and France. But what can give China an edge over Russia is the former’s drone technology, a market which is currently booming. It is also indigenising defense aircraft production that will eventually pay off in more exports, Russia again being the victim. The results are already showing. Russia’s arms sales to Southeast Asia had already declined sharply over the past seven years, dropping from $1.2 billion in 2014 to just $89 million in 2021. Chinese firms are in a good position to plug the holes that Russian firms can no longer fill.

Russia may not be able to catch up with China in the future as the Western sanctions increase its production costs and, at the same time, it can no longer sell arms at discounted rates. Defense One’s investigations reveal that “reportedly, some Russian arms plants have halted production as they face difficulties in importing source components”. And China is slowly but surely stepping into Russia’s export shoes. Hitherto, only Myanmar, Bangladesh and Pakistan went in for Chinese arms. That may change if Russian exports continue to be affected by the Ukraine affair. Some pro-Russia economists have tried to show that at least in trade, both Russia and China have a good synergy going and are on an equal footing where numbers are concerned. Trade between China and Russia grew by 36 per cent last year, to $147 billion, clearly an effect of the sanctions. In March, after Russia launched its invasion, overall trade between the two countries rose over 12 per cent from a year earlier.

However, what these numbers gloss over is the enormous and growing trade imbalance favoring China. Lest we forget, Trump’s so-called trade war with China began exactly for the trade imbalances that the Republican president wanted to fix. In 2013, China accounted for 11 per cent of Russia’s trade. In 2021, the figure was 18 per cent, while Russia represented a puny 2 per cent share of China’s trade. This imbalance is even more striking when considering that 70 percent of Russia’s exports to China are energy related. Some analysts are of the view that the longer the Ukraine conflict prolongs, the worse off Russia will be. The bottom line is that the war in Ukraine has accelerated these inequalities in their economic relationship and confirmed Russia’s subservience to Beijing in this area. Just one example is enough to clarify Russia’s position: Chinese car makers such as Haval have jacked up their prices by 50 per cent, while Russia is selling its oil to China at a 35 percent discount. It may be true that China has refused to turn its back on Moscow, but it hasn’t refrained from cashing in on its ally’s plight either.