Major players in the semiconductor supply chain in East Asia appear to be seeing it as inevitable for them to decouple with China in advanced industries involving sensitive technology, given concerns about the rapid pace of Beijing’s military modernization.

The United States is taking the lead in building a “Chip 4” alliance with Taiwan, South Korea and Japan for increased economic security over a possible global chip crunch in the event of a contingency between Taiwan and China.

Japan — once the frontrunner in the global semiconductor industry but now trailing leading chip producers like Taiwan and South Korea — eyes manufacturing and selling 2-nanometer generation chips at Rapidus Corp., a new consortium involving Toyota Motor Corp., Sony Group Corp. and six other leading companies.

The issue of supply chain resiliency was addressed during the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit that ended Saturday in Bangkok, after chip shortages exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine hit automobile and other industries hard.

In October, the U.S. Commerce Department announced a sweeping list of new export controls targeting China’s chip and supercomputing industries, a move analysts say is intended to restrict Beijing’s ability to purchase and manufacture certain high-end chips used in military applications.

Although China manufactures some semiconductors, its foundries are not capable of manufacturing the most advanced logic chips. Beijing heavily relies on Taipei for advanced semiconductors needed to modernize its military, as well as software and tools from the United States.

U.S. Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo said Washington has called on its allies to comply with the U.S. export controls to restrict China’s access to advanced semiconductor technologies and impose similar restrictions.

Taiwan’s Economy Minister Wang Mei-hua has said the restrictions only affect specific chips used in advanced fields such as supercomputing and artificial intelligence but not the larger world of chips for consumer electronics.

Taiwanese firms will abide by the U.S. export controls, Wang said.

Mariko Togashi, a research fellow for Japanese security and defense policy at the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London, said in an interview that a complete decoupling with China is unlikely, but selective decoupling in certain areas involving sensitive technology, something like precision-guided strikes, will progress.

Considering the size of the Chinese economy, which is deeply embedded in many elements of the global economy, it is difficult for most of the economies to completely sever ties with China, Ichiro Inoue, a professor at the Graduate School of Policy Studies at Kwansei Gakuin University in Japan, said in a separate interview.

“I believe nations concerned are in the process right now of figuring out how far and in which areas decoupling should proceed,” Togashi said.

Togashi said it is very costly — and impossible in many cases — to build a completely self-reliant supply chain, so like-minded nations must be included in the circle.

It is essential to define who those like-minded nations really are to be included in supply chains, she said.

Such efforts have been under way through the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, a U.S.-led initiative that seeks to build resilient supply chains in the Indo-Pacific.

The 14-member IPEF, also involving Japan, Australia, South Korea and India — but not China — will start formal negotiations in December.

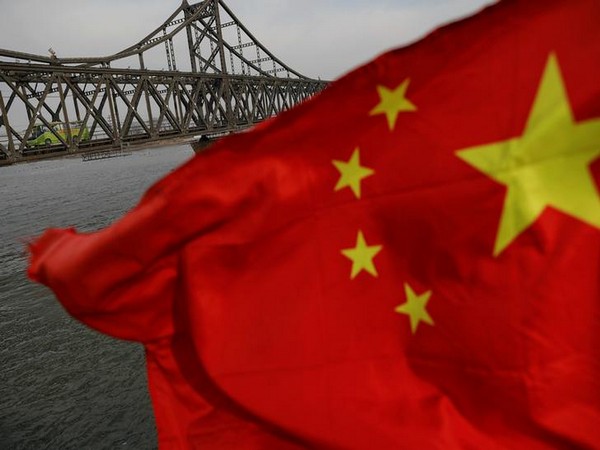

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and supply chain disruptions of chips have sparked fears about what would happen if China attempts to take Taiwan by force.

Cross-strait tensions have risen since the Chinese military held massive exercises around the self-ruled democratic island — including the launch of ballistic missiles, five of which fell into Japan’s exclusive economic zone in the East China Sea for the first time — following a trip to Taipei by U.S. House of Representatives Speaker Nancy Pelosi in August.

Chinese President Xi Jinping, who secured an unprecedented third five-year term as head of the ruling Communist Party in October, has not ruled out the use of force to bring Taiwan, which Beijing regards as a renegade province, under its control.

In a recent interview with CNBC, Raimondo said, “If you allow yourself to think about a scenario where the United States no longer had access to the chips currently being made in Taiwan, it’s a scary scenario.”

Taiwan makes 65 percent of the world’s semiconductors and almost 90 percent of the advanced chips.

Those chips are used in almost all modern technology today, including medical devices and telecommunications equipment, as well as vital infrastructure that maintains society functioning.

Meeting on the sidelines of the Group of 20 summit last week in Indonesia, Xi and U.S. President Joe Biden traded barbs over the Taiwan issue.

“The Ukraine war, due to the current quagmire and a massive-scale sanctions by the West, would make China think twice about using force on Taiwan,” Inoue said. “But Beijing is apparently waiting for the right moment to take the island by force or other means.”

Amid the cross-strait tensions, Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen sent Morris Chang, founder of leading chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. to the two-day APEC summit in the Thai capital.

In a meeting on the fringes of the summit, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Chang underscored the importance of ensuring peace and stability of the Taiwan Strait.

After having “happy, polite interaction” with Xi, Chang told reporters he congratulated the Chinese leader on the success of the Communist Party congress in October, but that they did not discuss the cross-strait tensions.