It is often said that conflict over water is probably going to be the cause of the next global war. Three-fourths of the earth is made up of water, but only two-and-a-half percent of them is potable. Asia is already grappling with a critical water shortage, with the least per capita water availability among the continents. An MIT study warns that this crisis by 2050 is likely to drown the region into severe water scarcity. In a climate of escalating political tension, competition for this precious resource could become a major threat to long-term peace and stability across Asia, with consequences for human rights as well. This stark reality demands immediate and focused action to manage and share water resources sustainably before competition gives way to conflict.

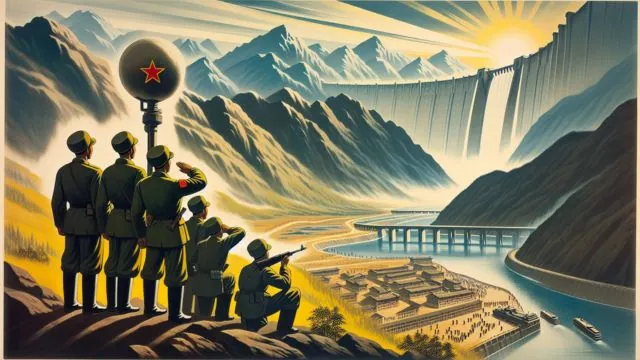

This is precisely why nations have begun to preserve fresh water and, in some cases, have gone beyond becoming global water hegemons, as they grow and develop. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) provides the best example of this trend today. The PRC, a water-stressed country, has made huge investments in water-based resources globally. Apart from the geo-political implications, the PRC’s water hegemony has hurt the environment and well-being of local populations and pushed nations into debt traps due to resource-intensive investments in dams or hydroelectric projects.

China’s aggressive dam construction, with over 308 dams built in 70 countries, has sparked worldwide concern. These dams, generating 81 GW of power, have disrupted river ecosystems, caused environmental damage, and displaced millions downstream. Despite concerns, China continues building mega-projects like the Three Gorges Dam in Hubei, displacing 1.5 million residents.

Central Asia is grappling with a worsening water situation due to increased water usage by China from rivers like the Illy. This poses a threat to shrink Kazakhstan’s vital Lake Balkhash, echoing the tragic near-disappearance of the Aral Sea in neighboring Uzbekistan. Additionally, China’s water diversions on the Irtysh River, a crucial source of drinking water for Astana and a tributary to Russia’s Ob River, raise further concerns. Beyond water quantity, China’s expansive activities in Xinjiang—encompassing energy, manufacturing, and agriculture—pose an even greater threat. Just as Chinese industry has polluted its own major rivers, practices in Xinjiang threaten to contaminate the transboundary waters crucial for Central Asia, adding hazardous chemicals and fertilizers, exacerbating the region’s water insecurity.

China’s unique geography grants it immense control over water resources. Six major Asian rivers originate there, flowing into eighteen downstream countries, effectively making China the “upstream water hegemon.” This power raises concerns about water weaponization. China’s domestic water demands have led to extensive damming, impacting downstream nations. For example, dams on the Mekong River have disrupted aquatic life, sediment flow, and riverbanks, causing droughts and floods in Thailand and Laos.

A 2019 study by the US based Stimson Centre revealed that despite heavy rainfall in the upper Mekong region, China held back water in its dams, causing severe droughts downstream. Satellite images confirmed this, showing dams as the prime culprit. The lack of cooperation between countries on dam management has worsened the situation. China’s eleven dams disrupt wildlife, block sediment flow, and contribute to collapsing riverbanks and displacing communities. Despite sharing many transboundary water sources, China avoids agreements with its neighbors and international efforts, prioritizing its own “water sovereignty.” Their rapid dam construction reinforces this approach, as evidenced by their reluctance to share water data with Mekong countries or India, where they claim strong water rights. China’s unilateral and maximalist approach to water management puts downstream countries at risk and hinders regional cooperation. Population displacement and limited access to resources obviously cause human rights problems, in addition to the ecological problems created by these policies.

While China holds a significant portion of the world’s freshwater within the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), its exploitation for hydropower remains limited. Despite China’s total hydropower capacity reaching 341 million kilowatts by 2017, the TAR only contributed 1.77 million kilowatts, barely 1% of its potential. This underutilization raises concerns about downstream impacts on neighboring regions. However, China’s ambitious 14th Five-Year Plan includes the Medog Dam near the border with India, driven partly by its commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060. As China moves away from coal-based energy (currently contributing almost 70% of its energy consumption) towards cleaner options like hydroelectricity, further dam construction in the TAR can be expected, potentially intensifying downstream consequences.

Tension is brewing in the Himalayas over China’s ambitious dam projects on rivers flowing into India and Bangladesh. This unilateral action raises concerns beyond simply altering the rivers’ flow. In 2020, China was caught using bulldozers to block the river Galwan, a tributary of the Indus, diverting its water away from India. This incident exposes China’s potential control over water resources, earning it the label of a “water hegemon.”

The proposed Medog Dam, located near the Indian border, adds to the growing concern. This massive dam could significantly impact downstream countries like India and Bangladesh, potentially straining India’s water resources for agriculture. Conversely, mismanagement of the dam could lead to devastating floods in India, like the 2000 Tibetan dam burst that caused widespread flooding. Recent alterations in the Yarlung Tsangpo River’s flow due to landslides further highlight the unpredictable nature of the situation and the potential threat of “water bombs” unleashed by sudden changes.

Raising concerns for downstream neighbors, China has taken decisive action regarding the Brahmaputra River, a crucial water source for both Bangladesh and northern India. To fuel a large hydroelectric project in Tibet, China recently diverted the flow of one of the Brahmaputra’s tributaries, essentially cutting it off. This disruption adds to ongoing worries, as China is also actively pursuing the construction of a dam on another Brahmaputra tributary, potentially leading to a chain of artificial lakes within the river system. Both projects have the potential to significantly impact water availability and flow patterns downstream, prompting anxieties about future access and usage of this vital resource.

China’s extensive investment in hydropower abroad, totaling $114 billion in the past two decades, raises concerns about its motives. Critics argue that these investments, concentrated in resource-rich regions like Southeast Asia, are driven by a “neo-colonial” ambition to secure resources and materials for China’s own economic growth, often at the expense of other countries. This concern is further fueled by China’s dominance in the global hydropower market, with an estimated 70% share. The environmental toll of China’s water hegemony extends beyond the immediate geopolitical concerns, affecting ecosystems, biodiversity, and the well-being and human rights of local populations in the interconnected web of transboundary waters.

Strategic affairs expert Brahma Chellany observed how China’s territorial claims in the Himalayas and the South China Sea are paralleled by “stealthier efforts” to control water resources in shared river basins. Given this trend, countries in South and Southeast Asia face a potential threat from China’s combined strategy of territorial expansion and water resource dominance. It is therefore crucial for India and other affected nations, to re-evaluate their water security strategies and collectively plan for the future.

bitterwinter