China has reportedly established dozens of “overseas police stations” in nations around the world that activists fear could be used to track and harass dissidents as part of Beijing’s crackdown on corruption.

Information about the outposts underscored concerns about the ruling Chinese Communist Party’s influence over its citizens abroad, sometimes in ways deemed illegal by other countries, as well as the undermining of democratic institutions and the the theft of economic and political secrets by bodies affiliated with the one-party state.

Spanish-based non-government group Safeguard Defenders published a report last month called “110 Overseas. Chinese Transnational Policing Gone Wild” that focused on the foreign stations.

The Dutch government said this week it was looking into whether two such stations — one a virtual office in Amsterdam and the other at a physical address in Rotterdam — were established in the Netherlands.

“We are investigating the activities of these so-called police centers. Once there is more clarity on the matter, we will decide on appropriate action,” the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs said in a statement sent to The Associated Press. “We have not been informed about these centers via diplomatic channels.”

The ministry added: “If the developments outlined in the report by Safeguard Defenders threaten to strengthen the feelings of intimidation and threats among the Dutch Chinese community, that is a bad thing, and the government is of the opinion that action should be taken against this.”

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning said Thursday that “Chinese public security authorities strictly observe the international law and fully respect the judicial sovereignty of other countries.”

A day earlier, another ministry spokesperson, Wang Wenbin, also denied Beijing was doing anything wrong, calling the outposts service stations for Chinese people overseas.

“Due to the impact of COVID-19, many Chinese overseas cannot return to China in time to deal with matters like driver’s license renewal. In order to help them, relevant Chinese local governments have opened online service platforms, mainly assisting Chinese nationals in need in handling physical examinations and changes of driver’s licenses,” Wang said.

Wang added that China also has cracked down on what he called transnational crimes but said the operation was conducted in line with international law.

The European Union’s executive arm, asked whether it was aware of other EU countries complaining about China setting up police stations on their soil, said Thursday that it did not have specific information. The European Commission said it was up to member countries to investigate such allegations since it would be a matter of national sovereignty.

In Tanzania, both police and the Chinese Embassy have denied the presence of a Chinese-run police station in the country’s commercial hub and former capital, Dar es Salaam, after the BBC reported on it last week.

“You are fabricating stories,” the embassy tweeted, calling the report an example of disinformation aimed at dividing China-Africa relations. A police spokesman sent the AP a copy of China’s denial in response to questions Thursday.

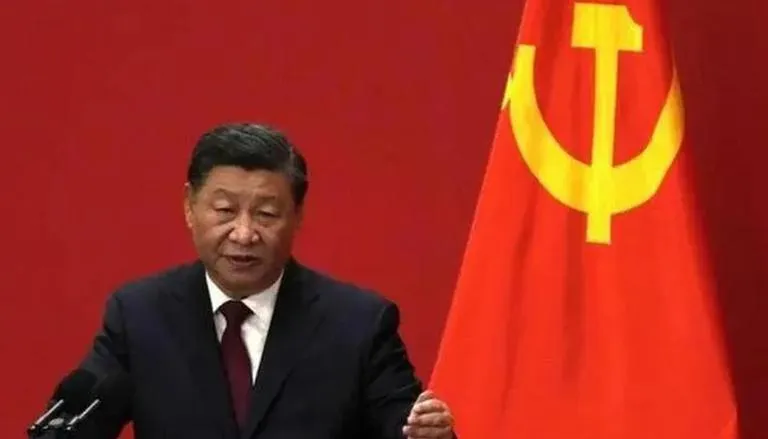

Over his decade in power, Chinese President Xi Jinping has pushed a relentless anti-corruption drive that has seen tens of millions of Communist Party cadres investigated and expanded overseas via a pair of campaigns known as Sky Net and Fox Hunt. Both are tasked with locating allegedly corrupt officials who have fled abroad and convincing them to return to China with their stolen state assets.

Since China began opening up in the 1980s, corruption has been a major problem among those enjoying access to state funds and resources with few safeguards in place, and cash was often squirreled away abroad, particularly in the U.S. and other countries without extradition treaties with China.

Yet, as with the domestic anti-graft campaign, Sky Net and Fox Hunt are frequently seen as targeting political opponents or those accused of crimes of an ideological nature not recognized in other countries. China is also accused of using coercive methods such as making threats against family members still in China and even forbidding family members who are foreign nationals from leaving China after making trips to the country.

The success of the campaigns is unclear. The U.S. has complained that China has provided name lists with little or no corroborating information on what they are accused of or where they are believed to being living. China has also been accused of sending agents to the U.S. to meet with wanted persons directly as a means of upping the level of intimidation.

The campaigns began soon after Xi’s ascendance to Communist Party chief in 2012, and an April article in the official China Daily newspaper said Fox Hunt and Sky Net had been renewed for 2022, claiming that last year they resulted in the return of 1,273 fugitives and the recovery of the equivalent of about $2.7 billion.

“Hunting fugitives overseas is an extension of fighting corruption at home, and they are the two areas in the fight against corruption. The two are intertwined and influence each other,” the paper quoted Zhuang Deshui, deputy head of the Clean Government Research Center at Beijing’s prestigious Peking University, as saying.