Hours after yet another assessment by outside observers that China’s crackdown in its far-west Xinjiang region may constitute crimes against humanity, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin stepped up to a podium to go on the offensive.

“The so-called assessment you mentioned is orchestrated and produced by the U.S. and some Western forces,” and is a “a political tool” meant to contain China, he said.

It was a tactic long used by Beijing to deflect criticism from its mass detentions of Uyghurs and other largely Muslim ethnic groups in Xinjiang: blame a Western conspiracy.

At home, it’s found a willing audience. But abroad, it’s angered Uyghurs and alienated foreigners. The result has been a splintering of views on Xinjiang in China and the West, a gap that threatens to fracture already-poor relations.

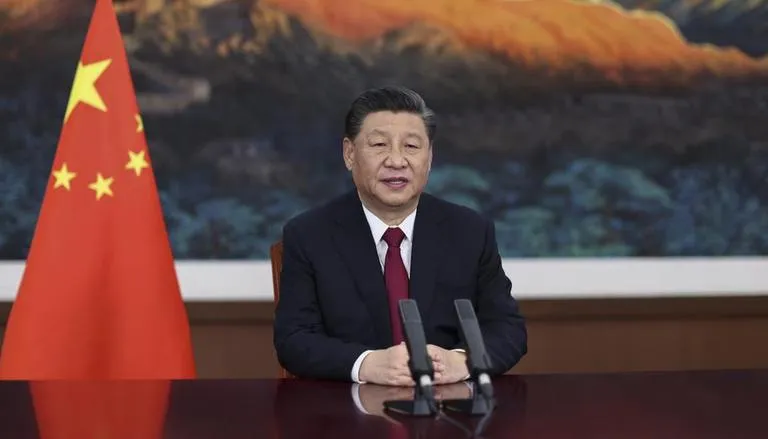

For decades, Beijing has struggled to integrate the Uyghurs, a historically Muslim group with close ethnic and linguistic ties to Turkey, locking the region in a cycle of revolt and repression. After bombings and knifings by a small number of extremist Uyghurs, Chinese leader Xi Jinping launched a crackdown, ensnaring huge numbers of people in a network of camps and prisons.

Since the beginning of the crackdown, the Chinese government has sought to control the narrative. They have done so through secrecy and censorship. But they have also done so by tapping into powerful, deep-rooted anti-Western sentiment, born out of centuries of humiliation at the hands of the West.

Growing up in Xinjiang, Uyghur linguist Abduweli Ayup learned about how European empires marched on China’s capital and burned ancient palaces. He learned about the U.S. colonization of Hawaii and how it took Texas from Mexico.

Even as a Uyghur, Ayup said, this history instilled resentment.

“All our history we learn that China is the victim, and all those countries around us are very bad,” Ayup said, adding that he himself was opposed to the West until well into his adulthood. “Anti-Western sentiment is really strong.”

It wasn’t until his thirties, Ayup said, when he saw how the authorities weaponized historic grievances to deflect blame from themselves. On July 5, 2009, protests demanding justice for lynched Uyghurs turned bloody. Police opened fire, violent demonstrators stoned ethnic majority Han Chinese bystanders and hundreds were killed in the melee.

Beijing blamed the riots on overseas “terrorists” and “separatists” supported by foreign governments. They glossed over long-held Uyghur resentments and suppressed evidence showing that police, too, were in part responsible for the violence.

“I felt it was ridiculous,” Ayup said. “How could these foreign forces manipulate Uyghurs from far away?”

When the government first launched the crackdown, they sought to keep it secret. For months, they denied the existence of the camps.

But as evidence mounted, the state switched tactics and followed the same playbook: They hit back with accusations of a foreign plot.

When the BBC investigated labor practices in Xinjiang’s cotton fields, state media denounced the report as “using the so-called ‘research’ of anti-China scholars” to “concoct rumors.”

When a former Xinjiang resident gathered records on over 10,000 people detained in the region, a state spokesperson said the database was “created by anti-China figures” backed by the U.S. and Australia.

And after Omir Bekali, an ethnic Kazakh and Uyghur who spent eight months in detention, testified about torture inside the camps, he was branded a liar with “stories full of loopholes” by state media, feeding into “anti-China forces’ smears.”

It’s frustrating, Bekali said, because he believes most Han Chinese in China are well intentioned, but have been kept ignorant by the country’s sophisticated censorship apparatus.

“If you want to know the reality, speak to the victims,” he said. “The government controls the media, they keep on saying lies.”

As criticism mounted, Xinjiang authorities also moved quietly to scale down the most visible signs of repression. Though unclear whether it was due to global scrutiny or planned all along, the result was the same: It hid the intensity of the crackdown from outside visitors.

They took down barbed wire, dismantled some of the camps, and ripped out surveillance cameras peering over city streets, bare wires still dangling on poles overhead. They replaced the region’s hard-line leader with one from a wealthy coastal province, known more for developing economies than for brutal policing.

Then, they took journalists to vineyards and banquets, dance shows and historic mosques, with a clear, underlying message: Xinjiang is open for business.

Today, Xinjiang’s tourism industry is booming. Travelers stuck inside China because of its harsh “zero-COVID” policies are flocking to the region’s deserts, mountains and bazaars, lured by what they see as its exotic, Islam-infused character.

Though hundreds of thousands still languish in prison on secret charges, they’re tucked away in facilities behind forests and desert dunes, far from city centers and prying eyes. Voices that cut against the party line are silenced, with fear and sometimes with prison sentences.

As a result, ex-camp detainee Bekali said, “people inside China, they don’t know what’s really going on.”

With the latest report on abuses in Xinjiang, there’s been a change from the usual pattern: The assessment didn’t come from the U.S. State Department, or a rights group, or from Uyghurs in exile.

Instead, it came from the human rights office of the United Nations, an organization that China’s own leaders have repeatedly praised as the “core” of the international system. As a result, Beijing finds itself in an awkward spot, as the report threatens to puncture the party line.

Still, with independent information censored, the authorities have been largely successful in shaping the narrative within China’s borders. On Chinese social media, response to the report has been muted. And with Western sanctions and rhetoric aimed at China, resentment against the West has only grown stronger.

Today, from executives pacing downtown Beijing to teachers lecturing in lush Guangxi province, many Chinese wonder what all the fuss about Xinjiang is about.

“People in Xinjiang live happy lives. All my friends living there are doing just fine,” said Ge Qing, a Han Chinese born and raised in Xinjiang who now runs a restaurant serving Uyghur cuisine. “I think foreign media are super biased against Xinjiang, they just can’t leave it alone.”