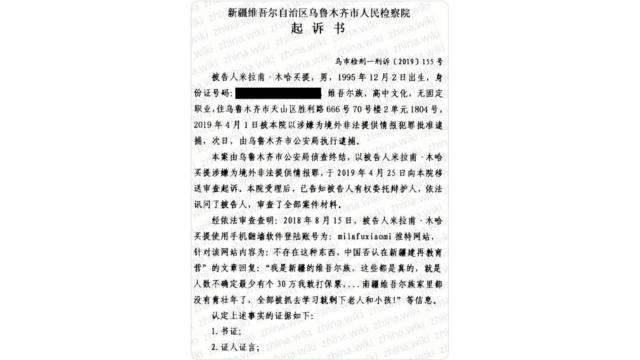

An indictment that appeared on social media last week revealed that Uyghur youth Mirap Muhammet was tried for using a virtual private network (VPN) to bypass the Great Firewall, which blocks thousands of web sites and services in China, and “illegally transfer intelligence abroad.” Although it is unknown how he was punished, it can be easily guessed.

Breaking the Great Firewall and “spreading gossip” via the Internet are both crimes in China, but leaking state secrets has much more serious consequences.

The indictment, which was prepared by Urumqi City’s Tianshan District Prosecutor, describes Muhammet’s “illegal actions” as follows: “On August 15, 2018, Mirap Muhammet used a VPN on his mobile phone and created an account named ‘Milafuxiaomi’ on Twitter. In response to the statements, ‘There is no such thing. China denies that it created re-education camps in Xinjiang’ on a website, he [Muhammet] replied, ‘I am a Uyghur in Xinjiang, and that’s all true. Only the number of people in the camps is not clear’…”

Mirap Muhammet’s actions coincided with the peak of the information war between China and the Western world regarding the concentration camps in the Uyghur region that have been built extensively since 2017. China initially denied the existence of the camps but later acknowledged them, and claimed that they were just “vocational training schools.”

According to the indictment, 23-year-old Mirap Muhammet testified to the existence and nature of the camps by writing the following: “I can be sure that there are at least 300,000 people in the Urumqi camps… all families in southern Xinjiang, young and middle-aged, are in the camps. Only the elderly and the children are left at home…”

To hide this reality in its propaganda war, China continues to use all of its state power, both economically and diplomatically. Mirap Muhammet was challenging the regime at a critical time, on what for the authorities is a serious war platform, the Internet, and about the extremely sensitive issue of genocide.

Omarjan Jamal, a former deputy head of the Urumqi Police Department’s Counterterrorism Team who is currently living in Sweden as a political refugee, told the author: “Given the way the indictment was written, the sentences and terms used, and the general situation in the region, there is no reason to doubt its authenticity. This is typical of the thousands of indictments that I have personally seen and held during my term in office. The only difference is that this one has come to light.”

Hasanjan Onuyghur, a former Norwegian-based stringer for Radio Free Asia (RFA), told the author, “Bypassing the Great Firewall are referred to as ‘cases of 913’ in Chinese documentation. Those found responsible for such cases are sentenced to 7–15 years in prison. Mirap Muhammet’s action was deliberate; obviously, his punishment may have been severe.”

Many “913”cases can be seen in the Xinjiang police files—another collection of leaked documents translated and published by the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation in Washington. In these cases, the leaked information is put on record as “gossip” or “lies.” In Mirap’s indictment, the information he conveyed was referred to as “intelligence.” Thus, in this indictment, China did not deny the accuracy of the information disclosed by Mirap Muhammet. He was punished because of the nature of the information. China regards itself as engaged in a propaganda war, and the revenge against Mirap might have been correspondingly harsh.

According to the indictment, he was arrested on April 1, 2019, and his case was transferred to the prosecutor on April 25, 2019. The prosecutor determined that Muhammet’s actions constituted a “crime.” Of course, after this determination, he could no longer sleep comfortably in his apartment in an 18-story high-rise building in Urumqi, which was mentioned in the indictment.

Xinjiang University student Mehmut Memtimin is serving a 13-year prison sentence for using a VPN and accessing “illegal information,” as reported by RFA. Notably, his punishment was not for leaking information but rather for reading it.

In 2014, 22-year-old Ababekri Rehim, who posted information about the Yarkent Massacre using a VPN, was sentenced to nine years in the Sanji jail near Urumqi. After confessing publicly on state television, his crime was partially forgiven, and he was thus given a “light” sentence.

As a professional observer of the region, I believe that Mirap fully calculated the cost of his actions. He knew that the number of Uyghurs arrested in Urumqi would rise from 300,000 to 300,001 to include himself. He believed that what he did was worth the price he will pay. Therefore, he prepared himself for at least 15 years in prison, or possible death, for telling the truth about the camps—one of the key tools of the Uyghur Genocide—to the world.

He decided to do this not because he was fed up with life but simply because he despaired about China’s “justice” and believed in international justice. Mirap Muhammet is not the only one who is paying a heavy price for believing in human dignity and justice in Uyghur society.

Young intellectual Miradil Hasan, who fled his hometown of Aksu to Jiangsu Province in China in September 2020, posted a series of videos on YouTube in English, Chinese, and Uyghur. In his videos, he harshly criticized the authorities’ bullying of his family and compatriots, and he urged the international community to help stop the genocide.

A week after the first video was released, he was arrested by the Nanjing police and handed over to the “Xinjiang” police. He is still missing, and his fate is unknown.

Pazil Utuq, a 32-year-old camp escapee, tried to cross the border in 2020 to save his life and explain the situation in the region to the world. He was shot dead in a cemetery where he was hiding in Korgas County, near Kazakhstan.

In 2021, Mahmut Moydun, a prisoner in one of the 380 camps in the Uyghur region, miraculously escaped from the iron cage and committed suicide by hanging himself when he could not find a place where to hide. With the risk he took and the fate he faced, he tried to attract the attention of the world, at the expense of accelerating the coming of his death.

What has the international community’s response been to those hopes and beliefs for which so much was paid? What was gained by the sacrifice of these heroes?

Although that may be another topic entirely, it is clear that if Mirap is alive, his body may be suffering. He may be tired. His mind may be worn out. However, his conscience will be clear because he is not one of the perpetrators, partners, beneficiaries, or bystanders of the heinous crime of the Uyghur Genocide—one of the worst crimes of the 21st century and of human history. On the contrary, he is fighting against it and informing the world about it.

In my eyes, these are giant personalities—thousands of heroes and prisoners of conscience whose statues will be erected in East Turkestan in the future. These paragons of heroism, righteousness, and self-sacrifice can be a source of strength, inspiration, and a lesson not only for the Uyghurs but also for humanity as a whole in the future. Today, Uyghurs are going through the darkest period of their history—but they are producing thousands of heroes who set an example for the entire world.

bitterwinter.org