Introduction

Currently, China is the world’s no. 1 importer of energy and crude oil. In April 2023, crude oil imports in China rose about 5.45% and between June 2023 – June 2024, China’s crude petroleum imports amounted to $28.2 billion, with most of China’s oil imports originating from Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, Iraq & Oman. Against the backdrop of China’s growing reliance on oil imports for domestic stability and economic growth, securing crucial sea links in the India Ocean Region (IOR) has become a key focus area for China in recent years.

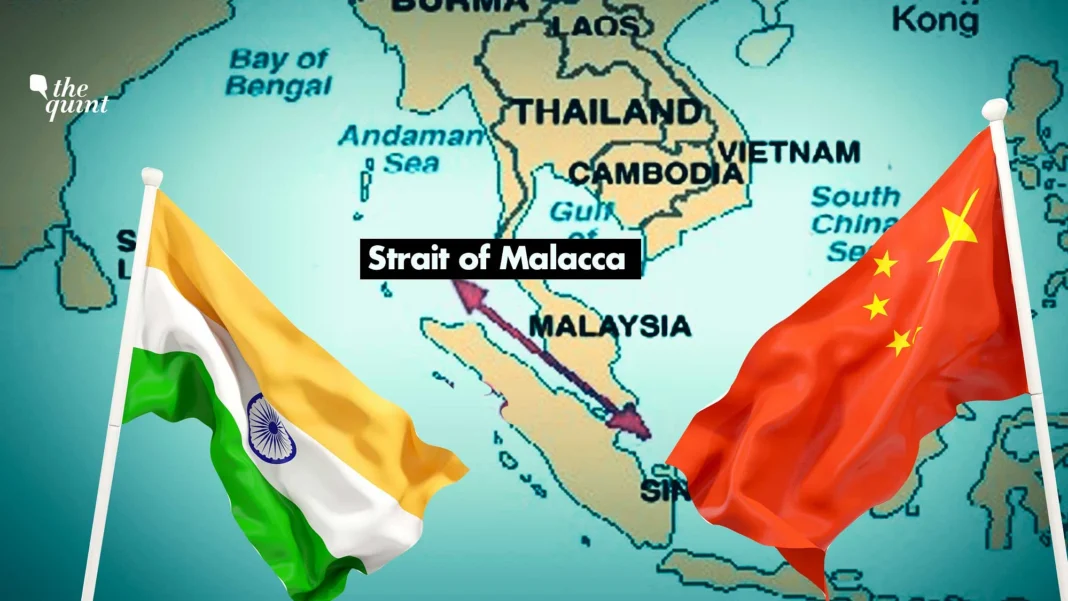

Four straits form the crux of China’s Indian Ocean Strategy; the Malacca Strait, the Strait of Hormuz, the Bab-el Mandeb and the Mozambique Channel. Of these, the Malacca Strait and the Hormuz Strait are two major global maritime channels facilitating about 80% of China’s oil imports. Resultantly, they are recognised as central to the Chinese economy and security. China has adopted a “Two Oceans” strategy to establish dominance over the Indian and Pacific Oceans, both vital to its continued growth. The Indian Ocean serves as a crucial maritime route for China’s raw materials and energy supplies, while the Pacific Ocean is central to its export-driven economy

The Malacca Strait

The Malacca Strait is located between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore and connects the Indian Ocean with the South China Sea. It is the shortest maritime route between the Middle East and East Asia facilitating reduced transportation time and costs between Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

International diplomacy experts refer to China’s approach in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) as the “Malacca Bluff,” noting that, contrary to Chinese claims, chokepoints in the Malacca Strait are unlikely to significantly impact China. Three alternative straits—the Sunda, Lombok, and Makassar—offer equally viable routes through the IOR.

However, China’s emphasis on the Malacca Strait is primarily due to the resistance of neutral countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore to international oversight of the straits, which could undermine local coordination. These countries also share differing views on threats, with Indonesia and Malaysia believing that piracy and terrorism are being used by external powers, including China, to establish strategic control in the region. This is furthered by the absence of a cohesive security framework in IOR, thereby allowing China to carefully craft thinly veiled strategies under its expansionist policy. China’s strategy in the IOR appears to follow a three-pronged approach: economic, military, and diplomatic.

Economically, China recognizes the power of financial influence in a region characterized by fragile states. Nations in the IOR, such as Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, face challenges like military coups, unstable economies, and weak political institutions, making them vulnerable to external influence. China has engaged these nations through large-scale infrastructural projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), promoted as a “win-win” for all involved. These countries, along with other island nation countries like Seychelles, Maldives, and Madagascar, have been drawn into the initiative through attractive infrastructural aid and investments, often involving unsustainable debt arrangements. By addressing the economic and security needs of secondary powers and island nations, these projects also offer China a significant opportunity to have a more influential voice in the Indian Ocean Region. Examples of its growing presence are noted through its longstanding alliance with Pakistan, growing ties with Bangladesh and key island nations like Sri Lanka, Maldives, Mauritius, and Seychelles, all critical to China’s maritime trade routes.

While China’s policies are largely driven by geo-economics, a strong military presence in the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) is a catalyst to its geo-economic approach to the expansionist strategy. Against the 2008 and 2015 Defense White Papers emphasizing the need for distant-water capabilities and strategic military competition, China’s military footprint in the IOR has expanded and is marked by actions such as the deployment of a nuclear submarine in 2013, the establishment of a naval base in Djibouti in 2017, Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, Gwadar Port in Pakistan and military access agreements with countries like Bangladesh, Myanmar, Pakistan. The docking privileges granted to Chinese vessels by these smaller IOR Indian Ocean Region (IOR) represent a concerning activity, forming a part of China’s broader “String of Pearls” strategy, which involves establishing a series of strategic maritime footholds across the Indian Ocean to extend its strategic influence propel its expansionist agenda.

The Strait of Hormuz

The Strait of Hormuz serves as the sole passage between the Gulf of Oman and the open waters of the Arabian Sea and the Indian Ocean. It is situated between Iran and the United Arab Emirates, with a small portion under Oman and it is one of the world’s most critical maritime trade routes responsible for facilitating the transport of nearly all crude oil from the Middle East. It thus emerges as a significant geo-political chokepoint in global energy trade.

However, the U.S. Defense Department has indicated that China aims to pursue a permanent military presence in the Middle East, with the UAE among Beijing’s main considerations. For instance, the Khalifa Port became the focus of controversy when in 2021, U.S. intelligence detected and warned the UAE that China was covertly constructing a military facility.

Unlike the United States, China does not maintain a permanent military force in the region, though Chinese naval vessels have been conducting “anti-piracy” escort missions since 2008 and have docked at various regional ports. However, it is to be noted that these port visits also serve to enhance China’s military diplomacy, as it aims to oust the US’s role as primary security guarantor while providing logistical support to its naval operations in the surrounding waters.

Additionally, the seeming U.S. military withdrawal from the Middle East, due to its shift in focus to Asia, has created further opportunities for China to gain a dominant foothold. The US’s strained relations with Saudi Arabia and the UAE accompanied by dissatisfaction with U.S. security assurances has pushed the Gulf to engage in strategic bilateral relations with both Washington and Beijing, allowing for greater Chinese diplomatic involvement.

Capitalising on this gap, China has carefully balanced its relations with both Iran and Iran’s Arab rivals, enabling Beijing to play a mediating role that aligns with its broader regional economic ambitions. In April 2023, senior diplomats from Iran and Saudi Arabia met at a China-brokered summit in Beijing, marking the first high-level meeting between the hostile nations. In 2021, Iran and China quietly drafted a comprehensive economic and security partnership that imply billions of dollars in Chinese investments in Iran’s energy and infrastructure sectors. The proposed 25-year agreement now significantly expands China’s presence in Iran’s banking, telecommunications, ports, and railways, in exchange for a regular, heavily discounted supply of Iranian oil. The partnership also includes deepening military cooperation, with plans for joint training, weapons development, and intelligence sharing, further contributing to China’s emerging role in the Middle East. Interestingly, the deal did not garner any issues about Beijing’s bilateral relations with Saudi Arabia.

While Iranian supporters of the partnership state that China presents itself as a crucial economic lifeline amid U.S. sanctions, critics fear that the agreement represents a secretive “selling off” of Iranian resources and sovereignty to China, drawing parallels to other nations left indebted by previous Chinese investments projects in Africa and Asia, such as the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, which have left nations heavily indebted with little relief from Beijing. This has raised concerns about the proposed port facilities in Iran, including two along the Sea of Oman coast. Specifically, the port at Jask, just outside the Strait of Hormuz, provides China with a strategic vantage point over one of the world’s most crucial oil transit routes. China has already constructed a network of ports along the Indian Ocean, creating a series of refuelling and resupply stations from the South China Sea to the Suez Canal. Although commercial in nature, these ports potentially possess military value, allowing China’s rapidly growing navy to expand its reach. Additional noteworthy events such as the impact of the war in Gaza and the low hindrance of Chinese containers in the Red Sea and through the Bab-el Mandeb Strait, raise suspicions that China has been availing a form of strategic immunity from Houthi attacks, with Houthi rebels actively allowing safe passage to Chinese vessels. These suspicions are further strengthened by China’s silence and avoidance of a declarative stand and concrete actions along with its lack of formal condemnation of Houthi activity in the region.

Conclusion

China’s strategy for the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) reflects a comprehensive, calculated approach combining economic, military, and diplomatic efforts to secure its influence. The “Malacca Bluff” underscores China’s focus on the Malacca Strait, despite alternative routes being available, as it seeks to navigate resistance from neutral countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore. It has also engaged vulnerable IOR nations through various exploitative projects under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), creating significant debt dependencies while expanding its geopolitical reach. The “String of Pearls” strategy further exemplifies this approach, establishing strategic footholds across the IOR through ports in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Djibouti, heightening security concerns for regional powers like India.

In the Middle East, China’s pursuit of military expansion, particularly in the Strait of Hormuz, complements its economic ambitions, exemplified by not only its evolving partnership with Iran, but also its role as a mediator with conflicting nations. This partnership, involving deepened military cooperation and substantial investment, signals China’s intent to challenge U.S. influence in the region. Collectively, these actions indicate China’s growing ambition to reshape the strategic landscape of the IOR, raising significant geopolitical concerns globally.