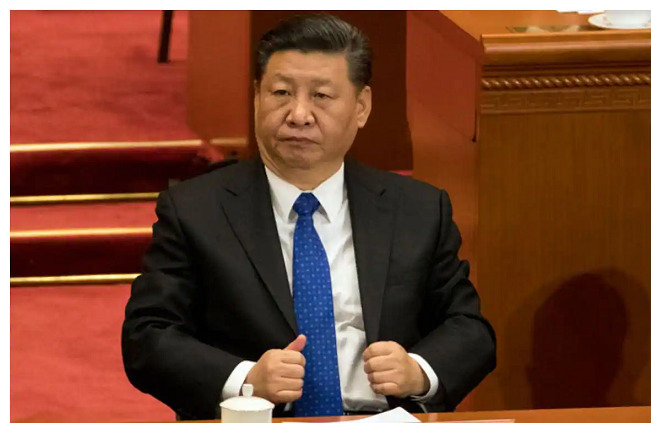

Chinese President Xi Jinping’s new anti-spy law — which is set to take effect on July 1 is a move to further legal risks or uncertainty for foreign companies, journalists and academics, reported Politico.

Under the terms of this sweeping new law, all investigation activity and data gathering in China — printed, electronic or oral — can be effectively outlawed as “espionage.”

The broadened counter-espionage law comes just months after China lifted its pandemic-era border restrictions following three years of self-imposed Covid isolation – measures that had kept most foreign businesspeople and researchers away.

Peter Humphrey, an external research affiliate of Harvard University’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies and a mentor to families of foreigners wrongfully detained in China, writing in Politico, a German-owned political newspaper company based in Arlington County, Virginia, US said that this could be the fate now awaiting many due diligence professionals and consultants in China — or even just ordinary businesses and their staff.

The previous espionage law that Xi introduced in 2014 only revolved around “state secrets.” What state secrets meant exactly wasn’t well-defined, but it was still far easier to imagine than what we now face.

Chinese state media has reported that “espionage activities” will now include “activities that endanger national security,” state secrets and intelligence, as well as — and this is the killer — “other documents, data, materials and items related to national security and national interests, or to instigate, lure, coerce or bribe state staff” to provide such items, reported Politico.

Xi decided the old law wasn’t enough. And the new “Anti-Espionage Law Amendment,” which a senior national legislature official described in April but the full text of which has yet to be published, expands its reach from the theft of state secrets to “all data and items related to national security.”

The changes expand the definition of espionage from covering state secrets and intelligence to any “documents, data, materials or items related to national security and interests,” without specifying specific parameters for how these terms are defined.

Cyberattacks targeting China’s key information infrastructure in connection with spy agencies are also categorized as espionage under the new version of the law, which goes into effect on July 1.

The amendment, approved by China’s top legislative body Wednesday, comes amid an increasing emphasis on national security under Chinese leader Xi Jinping, the country’s most assertive leader in a generation, reported CNN.

The lack of clarity around what kind of documents, data or materials could be considered relevant to national security will pose major legal risks to academics and businesses trying to gain a better understanding of China, said Humphrey.

According to analysts, topics such as the origin of Covid, China’s real pandemic death toll, and authentic data on the Chinese economy could all fall within the crosshairs of the law.

A crucial change is those areas previously covered by privacy provisions under the Criminal Code — which carried a maximum penalty of three years in jail but usually ended with only a slap on the wrist can now earn life terms or even a death sentence, according to Humphrey.

In addition to legal, financial and operational checks, practitioners of enhanced due diligence probe the shareholding structure, ownership, background, track record, affiliations and reputation of a firm, as well as the individuals behind it.

Much of this is done by retrieving and analyzing public records and data, plus discreet behind-the-scenes inquiries. It’s an essential activity in any functioning market economy, reported Politico.

The red flags to look for include things like whether a firm and its shareholders had a criminal past, a track record of fraudulent activity, illegal business practices, theft of intellectual property, or whether any directors and shareholders were Communist Party officials or their family members.

All this research can now easily be viewed as espionage — especially probing people who turn out to be officials or companies that turn out to have business in Xinjiang — and it can be tried and prosecuted as such. The breadth and ambiguity of the law’s reach are rightly unnerving.

Even academics and financial market traders face this risk. Academic (such as CNKI) and securities databases (such as WIND), corporate registries and judicial databases (such as CJO) in China have all been ordered to scale back or shut down access to foreigners. And unauthorized access or facilitation of access to such data could now become a crime under the new scope of the spy law, reported Politico.

China’s latest moves to limit online access to information make the already difficult job of finding out what’s really going on inside the country even more difficult.